Trinity's Triumph: Despite a daunting health journey, a wheelchair fencer sets her sights on the 2024 Paralympics

In a basement gym at St. Paul University, members of the Ottawa Fencing Club gather for an evening training session.

Competitors lunge, defend, and retreat, navigating the physical and mental obstacles of the sport.

There may be no one more equipped for those obstacles than Trinity Lowthian, strapped tightly in a wheelchair, preparing for her first bout of the night.

“She is the person who will do what it takes to be as good as anybody else, in light of any obstacle put in her way,” says Trinity’s mom, Heather Trail.

“She’s always tried her best to put in 110 per cent.”

Trinity is a fierce competitor with one goal in her sights.

“I want to qualify for the 2024 Paralympics in Paris,” she says.

Astonishingly, the 20-year-old is new to the sport.

“I only started fencing in May.”

She’s the first parafencer at this club, but coach Paul ApSimon says her fluid movements make her a natural.

“From the first day, it looked like Trinity had done this before,” said ApSimon.

“And from that first day, the progress has been very fast.”

At her first Pan American Championships in Brazil last fall, Trinity wowed coaches and competitors.

“I came back with four medals, including a silver and three bronze,” she smiles.

Trinity won 4 medals—three bronze and one silver—at the Pan American Championships in Brazil last fall. She has created a gofundme page, hoping for support. “After everything I have battled to make it here, we can’t allow money to be what stops me.” (Supplied)

Trinity won 4 medals—three bronze and one silver—at the Pan American Championships in Brazil last fall. She has created a gofundme page, hoping for support. “After everything I have battled to make it here, we can’t allow money to be what stops me.” (Supplied)

And this weekend, at a World Cup Event in Washington DC, where she earns points to support her Paralympic bid, Trinity placed 8th overall. That, for a relative newcomer, is a remarkable result.

“She’s willing to do what other athletes are not,” said ApSimon.

The reason for that is deeply personal. Trinity’s mom, Heather, explains.

“When I was taking Paul and Trinity to the airport when they went to Brazil, Paul said to Trinity ‘what was the last thing you competed in, Trinity?’ And she answered ‘I was competing for my life.’”

Trinity didn’t always use a wheelchair. For much of her youth, she was active and able to walk, run, swim and compete in able-bodied sports.

“From competitive swimming to water polo, triathlons, biathlons, and everything in between,” she says.

“Even in triathlons, when she was competing against adult women, she was medaling as a very young teen,” says mom, Heather Trail.

“She was the unstoppable kid. Absolutely.”

But in 2018, life as Trinity knew it, came to a stop. The once energetic athlete was unable to absorb nutrients from the food she ate to fuel her. She became inexplicably and increasingly malnourished, eventually unable to digest anything.

“In high school I started getting sicker and sicker, to the point where I spent most of Grade 11 and 12 in CHEO. It was initially just digestion and stomach issues. It eventually got worse and worse where I couldn’t eat anything by mouth,” she says.

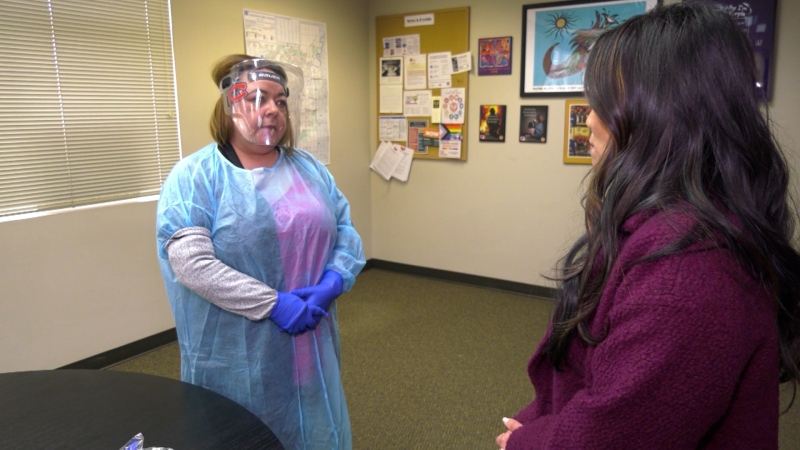

Trinity Lowthian during one of her many hospital stays in Ottawa. Trinity was later diagnosed with Autoimmune Autonomic Neuropathy, which prevents her body from regulating automatic bodily functions such as digestion. (Joel Haslam CTV Ottawa)

Trinity Lowthian during one of her many hospital stays in Ottawa. Trinity was later diagnosed with Autoimmune Autonomic Neuropathy, which prevents her body from regulating automatic bodily functions such as digestion. (Joel Haslam CTV Ottawa)

Unable to eat, Trinity became reliant on nasojejunal tube feeding. That’s when a thin, soft tube is inserted in the nose to the stomach and ends up in the jejunum—a part of the small intestine. But this attempt to nourish Trinity was also unsuccessful.

She’s endured countless trips to hospital and the ICU, and invasive tests and surgeries.

“She’s had 100 blood transfusions,” says her mom. “Unbelievable.”

“I ended up being diagnosed with a neurological disease that impacts all the nerves in my body that control all the automatic functions like your breathing, heartrate, temperature, bladder, your digestion,” Trinity explained. “All of that, my body couldn’t do or regulate normally.”

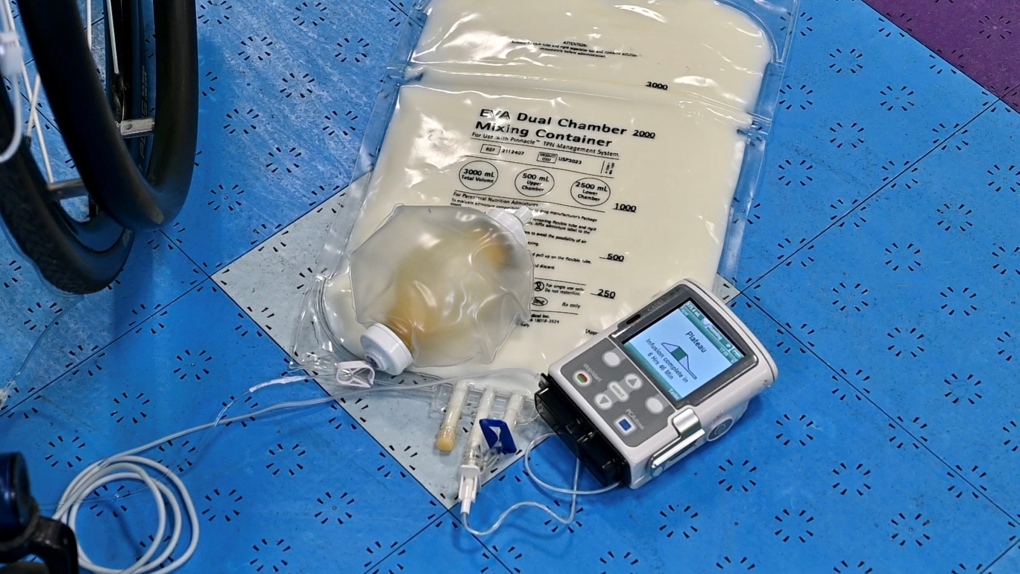

Trinity is living with autoimmune autonomic neuropathy. Its cause is unknown. Since 2020, her sole source of nutrition is Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN) supplemented with IV hydration. Nourishment is pumped from a bag she carries with her through a line directly into her heart.

Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN) is Trinity's sole source of nutrition, supplemented with IV hydration. (Joel Haslam CTV Ottawa)

Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN) is Trinity's sole source of nutrition, supplemented with IV hydration. (Joel Haslam CTV Ottawa)

In 2022, she also began receiving regular treatments of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) to bolster her strength. After her first treatment, Trinity battled meningitis and pneumonia. She eventually recovered and while her IVIG treatments have helped her become stronger, she now navigates life with a wheelchair.

“After the meningitis, it really started impacting how I walked and it affected my neurological system. That’s when I started using the chair a lot more. I’m in it full-time now,” she says.

There is no known cure for her condition. With the support of professionals, family, and friends, Trinity is learning to live with the challenges of her reality.

“There was probably a good three-, four-, or five-year adjustment period when I was not handling things very well. But part of what helped me get okay with myself was getting back into sports,” she says.

“That, and therapy. Lots and lots of therapy,” she continues. “I feel so much better when I focus on the positives. Focusing on the negatives brings me nowhere.”

While she’s in awe of her daughter’s courage, Heather Trail says watching Trinity’s daunting journey has been painful.

“It’s heartbreaking and there’s nothing you can do to make it better,” says Trail, her voice breaking.

“That’s why Trinity having this outlet with fencing is so helpful to me as well because I’m able to support her in this, which is something positive. I did go through four years of just supporting her and coaching her to get up in the morning and get on with her day and do it all again. Now, she has something to work towards, so every day when she gets up she has a purpose and she’s going for it,” she says.

“My mom has been my number one, best person by my side, forever. So, it’s been great having her be able to support me when I’m healthy and thriving, instead of dying,” Trinity laughs.

At St. Paul, Trinity trains using a customized and adjustable wheelchair fencing “field of play”.

“It’s locked in, so when you fence, you’re balanced,” says coach ApSimon.

“There’s no chance of you falling out of the chair.”

The training sessions are beneficial for Trinity, but they’re also very helpful to her able-bodied teammates, who take turns sitting and fencing in a chair opposing Trinity.

Trinity Lowthian (left) trains with an able-bodied fencer at the Ottawa Fencing Club. (Joel Haslam CTV Ottawa)

Trinity Lowthian (left) trains with an able-bodied fencer at the Ottawa Fencing Club. (Joel Haslam CTV Ottawa)

“We practice together and bout together. They get a lot of their hand skills from it because they don’t have the opportunity to run away. They’re stuck where they are. And for me, it gives me the chance to fence against people who don’t have an impairment,” Trinity says.

After conquering so many unfathomable obstacles, Trinity now faces another—financing. Wheelchair fencing on the world stage and travelling to where Trinity can face qualified competitors is prohibitively expensive.

She’s created a GoFundMe page hoping for support.

”My path to success will be costly, and parafencing is heavily underfunded in Canada. I train tirelessly with my coaches Paul ApSimon and Benjamin Manano at the Ottawa Fencing Club. There are no parafencing training camps or competitions in Canada, meaning I must travel internationally to qualify for the Paralympics. The 2023 World Cup season will see me competing in Washington, DC, Italy, France, Austria and Poland,” she says on her GoFundMe page.

While training four nights a week, Trinity continues her studies at the University of Ottawa in nutrition sciences. Her goal is to become a dietician.

“Not being able to eat and knowing how much my life has changed since getting proper nutrition, I know how important that is for everyone,” Trinity says.

For now, Trinity’s singular athletic focus is qualifying for Paris, vowing that nothing will stop her.

“I have no doubt about that,” says mom, Heather Trail.

“She’s setting her mind to it and it will happen.”

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Young people 'tortured' if stolen vehicle operations fail, Montreal police tell MPs

One day after a Montreal police officer fired gunshots at a suspect in a stolen vehicle, senior officers were telling parliamentarians that organized crime groups are recruiting people as young as 15 in the city to steal cars so that they can be shipped overseas.

'It was joy': Trapped B.C. orca calf eats seal meat, putting rescue on hold

A rescue operation for an orca calf trapped in a remote tidal lagoon off Vancouver Island has been put on hold after it started eating seal meat thrown in the water for what is believed to be the first time.

Man sets self on fire outside New York court where Trump trial underway

A man set himself on fire on Friday outside the New York courthouse where Donald Trump's historic hush-money trial was taking place as jury selection wrapped up, but officials said he did not appear to have been targeting Trump.

Sask. father found guilty of withholding daughter to prevent her from getting COVID-19 vaccine

Michael Gordon Jackson, a Saskatchewan man accused of abducting his daughter to prevent her from getting a COVID-19 vaccine, has been found guilty for contravention of a custody order.

Mandisa, Grammy award-winning 'American Idol' alum, dead at 47

Soulful gospel artist Mandisa, a Grammy-winning singer who got her start as a contestant on 'American Idol' in 2006, has died, according to a statement on her verified social media. She was 47.

She set out to find a husband in a year. Then she matched with a guy on a dating app on the other side of the world

Scottish comedian Samantha Hannah was working on a comedy show about finding a husband when Toby Hunter came into her life. What happened next surprised them both.

B.C. judge orders shared dog custody for exes who both 'clearly love Stella'

In a first-of-its-kind ruling, a B.C. judge has awarded a former couple joint custody of their dog.

Saskatoon police to search landfill for remains of woman missing since 2020

Saskatoon police say they will begin searching the city’s landfill for the remains of Mackenzie Lee Trottier, who has been missing for more than three years.

Shivering for health: The myths and truths of ice baths explained

In a climate of social media-endorsed wellness rituals, plunging into cold water has promised to aid muscle recovery, enhance mental health and support immune system function. But the evidence of such benefits sits on thin ice, according to researchers.