Researchers in Ottawa have found the "Achilles Heel" in an aggressive and deadly brain cancer.

The hope is that this may lead to new therapies for a cancer that kills 50 percent of patients within a year and a half.

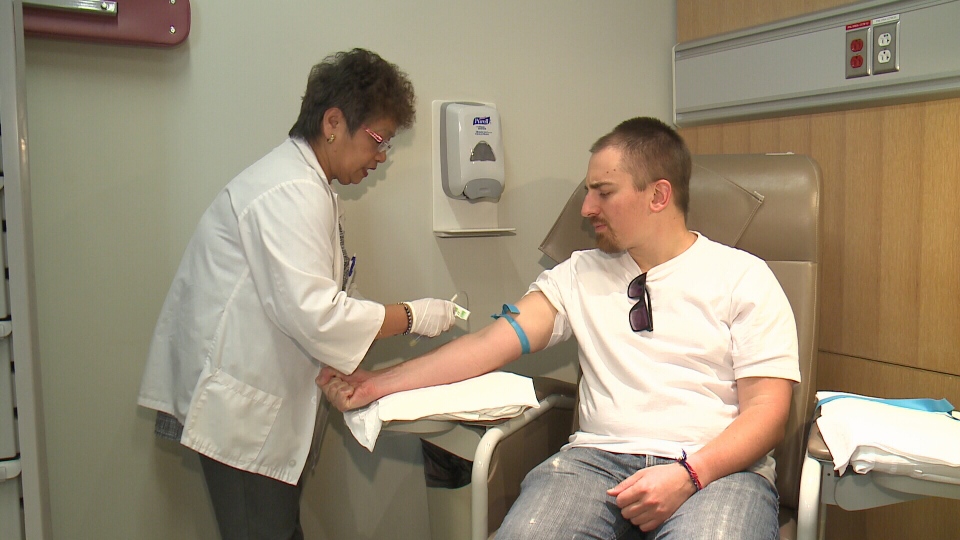

Once a month, 29-year-old Denis Raymond comes for blood work at the Ottawa Regional Cancer Centre.

It is a small inconvenience to make sure he is still healthy after a brutal diagnosis 3 years ago.

“I was in shock, scared,” says Raymond, “It's life shattering news to be told you have a 50% chance to make it to a year and a half. It threw my life out of balance.”

The young teacher was told he had glioblastoma, one of the most deadly brain cancers which is difficult to treat with surgery and resistant to radiation and chemotherapy. Raymond had a tumor the size of an orange surgically removed in May of 2013, followed by 32 rounds of radiation and 12 months of chemotherapy. Despite all that, he knows his cancer will likely return.

“I know it will come back and I have to live with that, until we find better treatments.”

Research done largely in Ottawa may hold out hope for treatment. They have discovered that a protein called OSMR (Oncostatin M Receptor) acts like an Achilles Heel in the formation of the brain tumor.

“If we block the function of this Achilles heel,” says Dr. Michael Rudnicki, the Director of the Regenerative Medicine Program at the Ottawa Hospital, “the tumor can't grow and disappears. This is all done in a mouse of course.”

The challenge now is developing drugs that will block that protein. Dr. Arezu Jahani-Asl was the lead author who performed the research under the supervision of Dr. Rudnicki. Dr. Jahani-Asl is now a principal investigator at the Jewish General Hospital, with a lab dedicated to how glioblastoma develops.

Their research, published today in Nature Neuroscience, leads to the possibility of treating other kinds of tumors like colon and ovarian cancer. But, Dr. Rudnicki admits, this is years away.

“Within our lifetime if it's all successful,” he says, “but it's a long difficult path to bring these treatments to clinic.”

So what does that mean for Denis Raymond? He believes it means hope.

“To finally be free of the constant worrying and constant thought of being faced with my own mortality, says Raymond, “It's very exciting, very exciting."