Ottawa-born scientist on turning agricultural waste into plastic alternative called 'Grasstic'

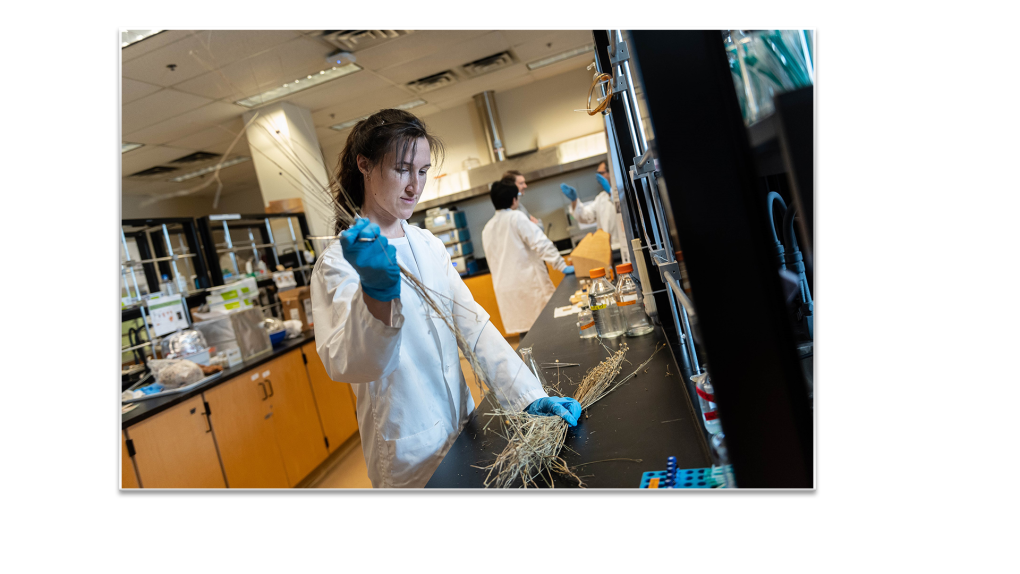

Amanda Johnson is a nature-loving biochemist working to create a plastic alternative from crop leftovers.

"When you spend time in nature you develop a relationship and want to protect it," says Johnson, an eloquent and ardent PhD student in the Faculty of Forestry at the University of British Columbia.

Johnson, a lifelong camper, hiker, nature lover and mother of two young children, who grew up in Ottawa and studied biochemistry at the University of Ottawa, is researching turning agricultural waste into an alternative to plastic.

She calls the product she developed, "Grasstic" - a bioplastic made from the residual stalks of crops like corn or wheat.

"It’s abundant agricultural waste and currently no-one is doing anything with it other than bailing it off the field or sometimes tilling it in," explains Johnson.

"I thought I’m going to play around with this in the lab and I did."

Johnson says she tried different formulation processes.

"And it was pretty amazing because I actually held this plastic in my hand thinking it looks like plastic, it feels like plastic. I knew I was onto something."

Ottawa-born, UBC PhD student in the Faculty of Forestry, Amanda Johnson, in the lab developing Grasstic. (Amanda Johnson and Daniela Camacho/submitted)

Ottawa-born, UBC PhD student in the Faculty of Forestry, Amanda Johnson, in the lab developing Grasstic. (Amanda Johnson and Daniela Camacho/submitted)

Johnson turned to her younger brother, David, for the name.

"He said, 'It’s made from grass, right?' I said, 'Yeah'. He said, 'call it Grasstic.'"

Grasstic stuck.

And 'fantastic' aspects of Grasstic were first learned when Johnson worked with grasses during her Masters.

"Grasses are made up of 20 per cent of the biopolymer called xylan and nothing is being done with it. It’s just a matter of getting it out of the plants and putting it into bioplastics," she says.

There are biodegradable plastic products out there but Johnson, committed to food sustainability, and conscious of food scarcity issues, wants to improve the options currently on the market.

"If you go to the store, you’ll be able to see biodegradable plastic bags that are made from plant polymers. The thing with these is that they’re made from corn, corn starch," says Johnson.

"When we start making packaging out of our food, we are going to run into problems with scarcity. We want to make them out of things that aren’t food."

The best uses for Grasstic, so far, are in packaging dry goods.

"Those films that you have on pastry products or dried goods boxes would be a perfect application for Grasstic."

Johnson demonstrates Grasstic being used to replace the plastic windows of pasta boxes and baked goods.

Those boxes then become totally biodegradable.

Johnson hosted a podcast about food, farming and sustainability and was motivated to get into the lab to create a new bioplastic when she learned the stats on plastics.

"Ninety per cent of the plastics we use, even the ones we put into the recycle bin, are never going to be recycled."

"They’re going to end up in an incinerator, or landfill, or worst-case scenario, contaminating our environment where they’ll stick around," says the research scientist.

Grasstic is now being tested for its rate of biodegradability.

"If you were to toss a Grasstic bag in your home compost, it would be completely gone in six weeks. If you sent it off to an industrial composting facility, it would be gone in four weeks," says the scientist.

"Currently, I'm testing how Grasstic biodegrades in the ocean. We are on day 95 of the experiment, and more than half of the Grasstic has biodegraded. So Grasstic is well on its way to being certified biodegradable.”

Amanda Johnson, biochemist and UBC PhD student, using agricultural waste to create bioplastic, Grasstic. (Amanda Johnson and Daniela Camacho/submitted)

Amanda Johnson, biochemist and UBC PhD student, using agricultural waste to create bioplastic, Grasstic. (Amanda Johnson and Daniela Camacho/submitted)

Why we need plastic alternatives

"Nature has no way of breaking down plastic," Johnson says.

"Plastics break down into microscopic pieces called microplastics."

"Microplastics get into our water and our food. Scientists are only beginning to understand the problems they cause when ingested."

Plastics are made out of fossil fuels, which are a non-renewable resource.

"Huge amounts of plastic have accumulated in the ocean. Sea animals such as turtles and albatross mistake plastic for food and it kills them."

Food wrapped in Grasstic, showing the potential 'future uses' of the bioplastic made from wheat and corn stalks, developed by UBC PhD student Amanda Johnson. Johnson is from Ottawa and did her degree in biochemistry at UofO. (Amanda Johnson/submitted)

Food wrapped in Grasstic, showing the potential 'future uses' of the bioplastic made from wheat and corn stalks, developed by UBC PhD student Amanda Johnson. Johnson is from Ottawa and did her degree in biochemistry at UofO. (Amanda Johnson/submitted)

That reality drives Johnson’s work. Her time in the lab for Johnson is fuelled by a lifetime spent outdoors.

"I’ve been close to nature my entire life. Growing up, my siblings and I spent countless hours playing in the forest behind our Ottawa home. My dad would take us biking along the Rideau Canal. My mom went camping with us."

And while Johnson, who now calls Victoria, B.C. home, reflects on that Ottawa past, she and her husband, Greg, are looking to create a promising future for their four-year-old, Millie and 15-month old Ori.

"Now that I'm a mom I want my kids to have the same chance to connect with nature. And that makes me passionate about preserving the environment."

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Trump threatens to try to take back the Panama Canal. Panama's president balks at the suggestion

Donald Trump suggested Sunday that his new administration could try to regain control of the Panama Canal that the United States “foolishly” ceded to its Central American ally, contending that shippers are charged “ridiculous” fees to pass through the vital transportation channel linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

Man handed 5th distracted driving charge for using cell phone on Hwy. 417 in Ottawa

An Ottawa driver was charged for using a cell phone behind the wheel on Sunday, the fifth time he has faced distracted driving charges.

Wrongfully convicted N.B. man has mixed feelings since exoneration

Robert Mailman, 76, was exonerated on Jan. 4 of a 1983 murder for which he and his friend Walter Gillespie served lengthy prison terms.

Can the Governor General do what Pierre Poilievre is asking? This expert says no

A historically difficult week for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his Liberal government ended with a renewed push from Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre to topple this government – this time in the form a letter to the Governor General.

opinion Christmas movies for people who don't like Christmas movies

The holidays can bring up a whole gamut of emotions, not just love and goodwill. So CTV film critic Richard Crouse offers up a list of Christmas movies for people who might not enjoy traditional Christmas movies.

More than 7,000 Jeep SUVs recalled in Canada over camera display concern

A software issue potentially affecting the rearview camera display in select Jeep Wagoneer and Grand Cherokee models has prompted a recall of more than 7,000 vehicles.

'I'm still thinking pinch me': lost puppy reunited with family after five years

After almost five years of searching and never giving up hope, the Tuffin family received the best Christmas gift they could have hoped for: being reunited with their long-lost puppy.

10 hospitalized after carbon monoxide poisoning in Ottawa's east end

The Ottawa Police Service says ten people were taken to hospital, with one of them in life-threatening condition, after being exposed to carbon monoxide in the neighbourhood of Vanier on Sunday morning.

New York City police apprehend suspect in the death of a woman found on fire in a subway car

New York City police announced Sunday they have in custody a “person of interest” in the early morning death of a woman who they believe may have fallen asleep on a stationary subway train before being intentionally lit on fire by a man she didn't know.