There's some encouraging news tonight for people with acute leukemia whose disease won't go into remission. Researchers in Ottawa say they have been blown away by a possible new treatment. It's a complicated story with an array of bizarrely coded proteins and genes. But one number stands out: a one hundred percent remission rate for all the animals treated.

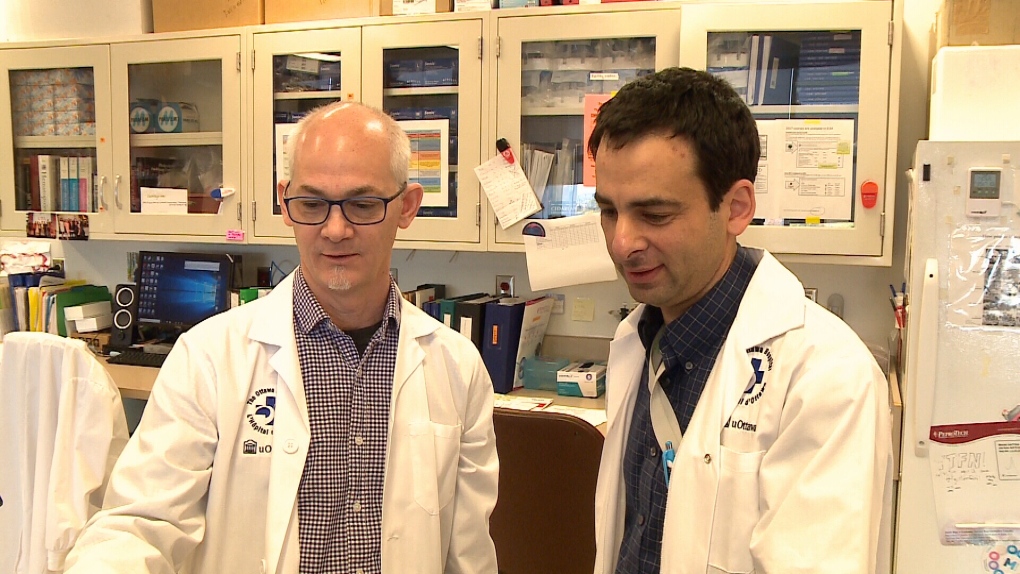

Cancer researcher Dr. William Stanford is used to examining cancer cells but recently, he was forced to examine his feelings after losing two close friends to this disease.

“My life's work was to prevent deaths like this,” says Dr. William Stanford, a senior scientist at the Ottawa Hospital, “I would say I was angry. I was angry at cancer and I felt I hadn't done enough.”

His first move was an impulsive one was a tattoo that gives the metaphoric finger to cancer and includes some colorful dots that represent his research.

“Adding this to my tattoo,” he says, “It really gave some positive hope for a potential treatment for cancer.”

His next move, a longer, more methodical one, was his research, teaming up with Caryn Ito, a senior investigator at the hospital and Stanford’s wife, along with Dr. Mitchell Sabloff, the Director of the Ottawa Hospital’s Leukemia Program and Co-Director of the hematology bio-bank. Their research, just published in the leading cancer journal Cancer Discovery, is aimed at figuring out why one-third of patients with acute myeloid leukemia, a deadly leukemia, failed to go into remission despite chemotherapy.

“In the end,” says Dr. Stanford, “we found that a protein was missing from one group of patients, but was there in another group of patients.

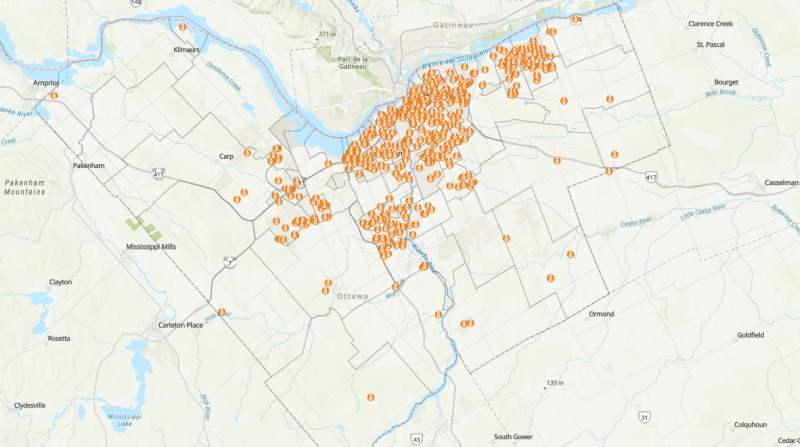

The patients missing the protein, MTF2, didn't respond to therapy. So, researchers, using samples from patients treated at the Ottawa Hospital, found that people with normal MTF2 were three times more likely to be alive five years after their initial chemotherapy treatment than those with low MTF2.

“What we found,” says Stanford, “is that this important protein, if we could restore it, we could treat these patients. And it just so happens that there’s a new drug being used in clinical trials that targets the protein we needed to target that.”

Using this new drug, researchers transplanted patient cells into mice, let them get sick and treated the mice just as they would treat the patients.

“We found that those mice that got their new combination chemotherapy, they survived,” says Dr. Stanford, “All of them; 16 out of 16 mice all survived.”

The researchers were blown away by the results. They want to start clinical trials on humans as soon as they can.

That will be Dr. Mitchell Sabloff’s role.

“We're all very excited by what we've discovered and we're actively trying to translate that back now,” he says, “We've moved it from the clinic to the lab and now we want to move it from the lab to clinic to help patients.”

For Ottawa resident Craig Osborne, it's amazing news. He was diagnosed with two types of acute leukemia and donated bone marrow to help with the research. Osborne is in remission.

“I think it's fantastic,” he says of this research, “Anything good that can come of what I went through is great.”

Dr. Sabloff says they will need hundreds of patients and many centres to conduct the clinical trials. The hope is to come up with a test that can help them determine which patients would benefit and a treatment to help patients who have no hope right now.