We all know the law of gravity: what goes up must come down.

But now there may be a new law: what goes down sometimes shouldn't.

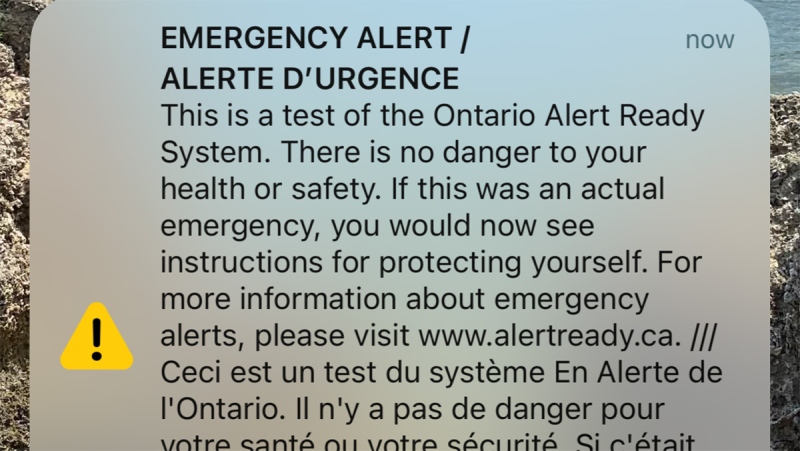

The city of Gatineau wants residents to push the pause button before they push the toilet handle.

It's a place we all use but few of us visit. Today, members of the media got a chance to tour Gatineau's sewage filtration plant and learn the ins and outs of what goes in and out of us.

“This is the first step of screening the waste water that comes in,” explains Guy Cregheur, the division head of Gatineau’s Waste Water Treatment Plant, as he guides the media around the facility.

But this tour has a purpose: to teach people what's okay to flush down the toilet and what isn't.

“It's not a garbage, it's a toilet,” Cregheur says, “Only 3 things go into toilet and needless to say what it is,” he laughs.

Those 3 things, urine, feces and toilet paper, are fine; it's the dental floss, the hair, condoms, sanitary products and wipes that are clogging waste water plants and causing massive repairs.

“It's not magic, it doesn't disappear, it comes here,” says Cregheur.

In fact, they produce a bag full of items that have come there, after being flushed down the toilet. They include a toy car, some balls, a vibrator, an iPhone, and even some dentures.

The coarse and fine screening stations catch some of it, but not all. Then it is literally all hands on deck, as operators are calling in to rake the globs out of the water and into a wheelbarrow for disposal.

“There's no mechanical device that will rip out the big chunk out of the propeller,” Cregheur explains, “We have to do that by hand.”

Those chunks on the propellers can get so heavy, they block the equipment. So at least twice a year, they use a crane to in to lift the agitators and clean them. Cregheur estimates it costs about $100,000 a year just to maintain and repair the equipment. Within the next three years, the city will spend about $7.45 million dollars to install even more screening devices to try to catch even more debris.

The end result of all this screening and cleaning, and messaging about what not to flush, is hopefully a pure product by the last spot on the tour. The facility is the biggest in Quebec and uses only biological agents, no chemicals, to treat the waste water.

“And then the water ends up in the river,” says plant operator Jacques Robinson, “in the Outaouais River, nice and clean.”

Surprisingly, not all our waste is wasted. That methane gas we humans create is actually recaptured and used to heat the entire waste water facility. So, in a sense what goes down kind of comes back up.